PHOENIX — The voting locations that experienced problems on Election Day in Maricopa County, home to more than half of Arizona’s voters, do not skew overwhelmingly Republican, according to an analysis by The Washington Post.

The finding undercuts claims by some Republicans — most notably Kari Lake, the GOP nominee for governor, and former president Donald Trump — that GOP areas in the county were disproportionately affected by the problems, which involved a mishap with printers. Republicans nonetheless argue that their voters were more likely to be affected, given their tendency to vote on Election Day rather than mail in their ballots.

Get the latest 2022 election updates

End of carousel

The claims come as Lake continues to narrowly trail her rival, Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, and as the number of ballots remaining to be counted dwindles.

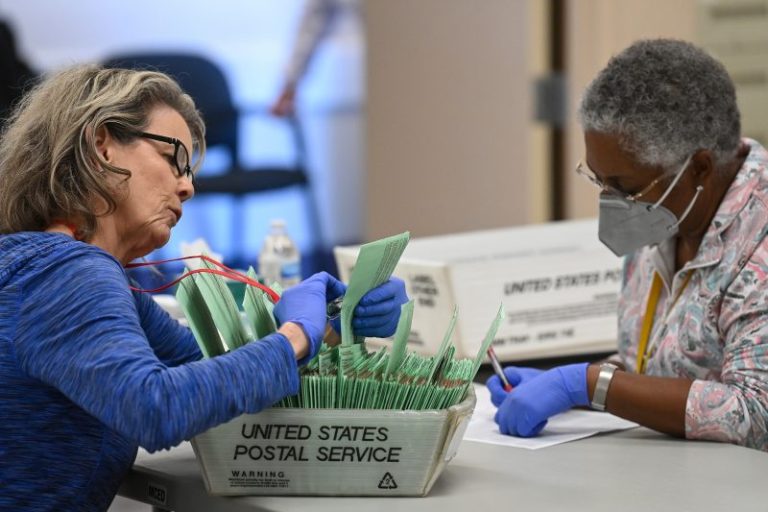

Starting early on Tuesday, printers at 70 of the county’s 223 polling sites produced ballots with ink that was too light to be read by vote-counting machines, which caused ballots to be rejected. That forced voters to wait in line, travel to another location or deposit their ballots in secure boxes that were transferred to downtown Phoenix and counted there. County officials say no one was denied the right to vote.

The Post identified the precincts of affected voting locations using data provided by Maricopa County election officials and then examined the voter registration breakdown within each precinct using data from L2, an election data provider.

The analysis found that the proportion of registered Republicans in affected precincts, about 37 percent, is virtually the same as the share of registered Republicans across the county, which stands at 35 percent.

Throughout the week, prominent Republicans suggested without evidence that the problem with printers only affected Republican areas.

Lake, addressing reporters after voting with her family at a site downtown, said, “There’s a reason we decided to change locations — we were going to go to a pretty Republican area.” Instead, she said, “We came right down to the heart of liberal Phoenix to vote because we wanted to make sure that we had good machines.”

“And guess what?” she added. “They’ve had zero problems with their machines today. Not one machine spit out a ballot here today. Not one, in a very liberal area. So we were right to come and vote in a very liberal area.”

In fact, there were problems at locations in precincts that skew heavily Democratic, according to The Post’s analysis.

They included two elementary schools in east Phoenix and a health center in south Phoenix — all locations where the share of Democrats outnumbers Republicans by about 40 percentage points. At the Mountain Park Health Center in south Phoenix, which was among the precincts that experienced issues with printers, there were nearly three times as many votes for Lake’s Democratic opponent, Hobbs, as there were for the Republican candidate, according to results released by the county.

A spokesman for the Lake campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Lake’s claims were amplified throughout the weekend by Trump, who wrote on Truth Social, the social media site set up by the former president and his allies, that “Even Kari Lake was taken to a Liberal Democrat district in order to vote.”

The former president used that assertion to push an unfounded claim that Maricopa County officials “stole” the election from Blake Masters, the GOP nominee for Senate. Masters on Friday was projected to lose his race to the incumbent Democrat, Mark Kelly.

“So in Maricopa County they’re at it again. … but only in Republican districts,” wrote Trump, who made the county a target of his false claims of election fraud in 2020.

He concluded, “Do Election over again!”

Masters hinted at a similar demand in an appearance Friday on Fox News host Tucker Carlson’s show, before his race was called by the Associated Press. “I think the most honest thing at this point would be for Maricopa County to wipe the slate clean, just take all the ballots and do a fresh count,” he said.

Masters claimed that the county had “mixed up” ballots on two occasions but did not offer a basis for that assertion. A campaign spokesman did not respond to a request for the evidence underlying his claims.

A spokeswoman for the county’s elections department said that poll workers at two locations had combined two batches of ballots but that “this has happened in the past, and we have redundancies in place that help us ensure each legal ballot is only counted once.” Those redundancies, which include checking total ballots against check-ins at voting locations, are carried out “with political party observers present,” added the spokeswoman, Megan Gilbertson.

In a statement posted Saturday on Twitter, Masters did not push fraud claims but said he would not concede until all votes had been counted.

Maricopa County officials have stressed in recent days that the glitches did not cause any ballots to be misread or block anyone from voting. They say they are working as long as 18 hours a day to process a record number of ballots dropped off on Election Day — and they have said for weeks that tabulation could take as many as 12 days.

“I’m going to stand up for my state,” Bill Gates, the Republican chairman of the county board of supervisors, told reporters on Friday afternoon. “We’re doing things the right way.”

Leaders of the Arizona Republican Party maintain that their voters were disproportionately affected by the glitches because of their tendency to vote on Election Day. “It was no secret that Republicans intended to vote on Election Day,” the state party said in a statement issued on Sunday.

But The Post’s analysis found that the proportion of Republican Election Day voters in precincts with printer problems was virtually the same as the share in precincts countywide, bolstering the county’s argument that people in affected areas who wanted to vote on Tuesday were not prevented from doing so.

Attorneys for the party asked a judge on Tuesday night to require county officials to extend voting times by three hours, citing the mechanical problems. But about five minutes before the polls were set to close, the judge denied the request, finding that Republicans were unable to show that any voter had been denied the ability to cast a ballot.

In Maricopa, voters can cast their ballots at any polling center, no matter where they live. It’s different from some systems that require people to cast their votes at designated locations near or in their neighborhoods.

Voters who live in the suburbs and drive into downtown Phoenix for work, for example, can cast their ballots either near their home, in the city’s center or at schools, churches or any of the 223 polling locations set up throughout the vast county.

Traditionally, people tend to vote in areas close to their homes or in locations that are part of their daily routines, said political scientist Michael McDonald of the University of Florida.

“The vote centers are conveniently located, they’re part of your day, they may be on your route for all of your errands,” he said.

Bronner reported from Washington. Jon Swaine and Reis Thebault in Washington contributed to this report.