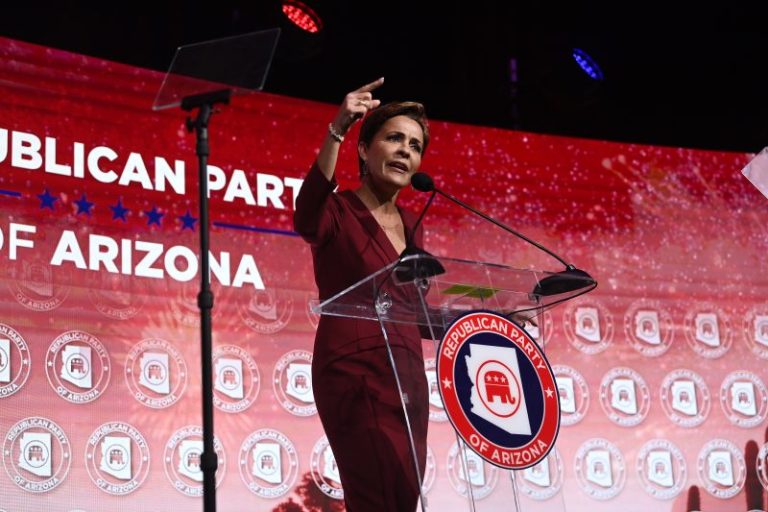

If there was a quip that defined Kari Lake’s now-failed 2022 campaign for governor, it was what she said about the late Sen. John McCain.

“We don’t have any McCain Republicans in here, do we? All right, get the hell out,” she said as far back as December 2021, adding: “Boy, Arizona has delivered some losers, haven’t they?”

Like much of Lake’s campaign, it was a page ripped out of Donald Trump’s playbook. Trump continued to rail against McCain even after his death, using the decorated war hero and moderate to set up a foil for his MAGA movement and push the bounds of good taste.

But it was certainly a curious move in a state that repeatedly delivered McCain double-digit margins. McCain fell way out of favor with the GOP both nationally and in Arizona by standing up to Trump and voting against the bill to repeal Obamacare; one poll conducted shortly before his death showed just 20 percent of Arizona Republicans had a favorable view of him. But plenty of Arizona Republicans, and especially independents, still liked him. A Fox News poll conducted in April 2019 — as Trump continued attacking a dead man — asked Americans whether they admired McCain or Trump more. They picked McCain 51 percent to 27 percent. Independents sided with McCain 51-13.

Whether that quip was pivotal for Lake or not, it was emblematic of her entire campaign. After winning their primaries, Republicans in swing states backed off their election denialism, support for banning abortion and enthusiasm for Trump. Lake bearhugged all of it till the bitter end. Lake attacked McCain while fending off a primary opponent, and apparently intended to keep running that kind of campaign even when the electorate changed.

A few examples, compared to the electorate Lake was appealing to:

As recently as October, her campaign voiced support for an 1864 Arizona law that banned abortion except to save the life of the mother — though at other points Lake indicated she supported rape and incest exceptions. Arizona voters on Election Day said abortion should be legal in most cases by a 62-35 margin, according to exit polls.In her final rally before Election Day, Lake concluded by pointing at the assembled media and saying, “These bastards back there don’t want us talking about stolen elections.” The same exit polls showed Arizona voters said 63-35 that President Biden was legitimately elected, and 73 percent said they were confident that elections in Arizona — whose 2020 results Trump baselessly sought to overturn — were fair and accurate.Many Republicans steered clear of embracing Trump too much at the tail end of the campaign — and even excised him from their websites after winning their primaries. But Lake not only welcomed Trump to a rally in early October; she took care to be photographed vacuuming a piece of red carpet for him. But just 17 percent of Arizona voters said their vote last week was to support Trump, and 57 percent of voters had an unfavorable view of him.She featured the support of fringe figures like Stephen K. Bannon and state legislator Wendy Rogers late in the campaign. And she continued to deride the “McCain machine” even after winning her primary. Exit polls show Lake lost moderate voters by 20 points, which was slightly larger than the GOP’s 15-point deficit nationally.

For a time, it looked like Lake might parlay this approach into becoming the MAGA movement’s next great hope — the rare election denier and firebrand who could marry Trump’s approach with an actually compelling candidacy capable of swing-state victory. Even in defeat, she performed better than many MAGA candidates in swing areas.

In the end, though, her loss put a stamp on an absolutely brutal election for her ilk.

Non-incumbent election deniers went 0 for 15 in governor’s races, and it wasn’t much better elsewhere. While some won, that came almost universally in red states, and the vast majority of them ran behind most standard-issue Republicans who appealed more broadly to a relatively evenly split electorate.

And despite running ahead of fellow MAGA Republicans like Blake Masters in the state’s Senate race and Mark Finchem in the secretary of state race, Lake still lagged much of her party and lost a very winnable race. The state GOP won six of nine races for the U.S. House and is running ahead of their 2020 presidential margins in five of seven contested races. And state Treasurer Kimberly Yee — the one statewide Republican not endorsed by Trump — won by double digits. (All of these results undercut whatever Lake might be about to claim about the election being stolen from her.)

Much like Trump’s 2016 and 2020 campaigns, the conceit of Lake’s run was that a Republican could cater extensively to the extremes as long as they are personally compelling. And that might have been a fair bet in Arizona, where the state’s conservatives have long been further to the right than the state’s makeup would suggest.

But like many in her party, Lake banked on a red wave that never arrived. That red wave could have propelled her to instant stardom on the national GOP stage. But instead it fizzled — in large part thanks to candidates like Lake.