Joe Biden shook hands with Xi Jinping that day in 2011 and the two vice presidents walked up a red carpet to the strains of their countries’ national anthems, until Biden paused unexpectedly before a Chinese official with a full head of hair. “If I had hair like yours, I’d be president,” he cracked, breaking the atmosphere of stately diplomacy.

Later in the whirlwind trip, Biden made a more serious point: “President Obama and I want to see a rising China. We don’t fear a rising China.”

More than a decade later, the two men are slated to meet again after Biden arrives Sunday night in Bali, their first face-to-face meeting since Biden became president and Xi consolidated his position as the strongest Chinese leader in recent memory.

Biden certainly has not acquired the thick mane of the Chinese diplomat. His administration now very much does fear a rising China. And U.S. officials are hoping that — somehow — the personal connection the two men forged more than a decade ago can soften the often hostile, sometimes volatile and potentially dangerous standoff between two global behemoths.

The Biden-Xi meeting is perhaps the most consequential encounter of a six-day foreign trip that will circumnavigate the globe, and it comes at the fulcrum of Biden’s presidency. He departs just after voters delivered a verdict on the first two years of his tenure, giving him better-than-expected results but possibly costing Democrats control of at least one chamber of Congress.

It also comes as the Pentagon issues fresh warnings that China poses the “most comprehensive and serious challenge to U.S. national security.” With colliding positions on trade, Ukraine and especially Taiwan — and even fears of a global U.S.-China cold war — the pressure on Biden could hardly be greater.

The question, diplomats say, is whether their old connection can be enough to mitigate the bitterness of the rivalry between the two superpowers.

“We’re in an awful dynamic, and what is being put to the test is whether there is enough of a relationship, enough respect and ability to listen,” said Daniel Russel, a U.S. diplomat who helped plan Biden’s trip to meet with Xi in 2011. “There’s something there. These guys really do know each other. And they have a legacy, a relationship.”

He added, “It’s the one thing we have to work with — that is kind of the only thing we’ve got going for us in slowing the death spiral of the U.S.-China relationship.”

While Biden arrives at the Group of 20 summit in Bali with new political challenges after democratic elections put Republicans on the verge of a House majority, Xi comes strengthened, just weeks after steamrolling any opposition to extend his autocratic reign by at least another five years.

“Xi Jinping is feeling all-powerful in his internal politics,” said John Delury, a professor of Chinese studies at Seoul’s Yonsei University. “China is rising and feeling stronger and stronger in the relationship, and Xi is going to bring that into his meeting with Biden.”

The tension between the two leaders’ identities lent drama to their 2011 encounter and may do so again this week. One is a devoutly Catholic Irish American who prides himself on a middle-class upbringing and a jovial persona. The other is a faithful Communist Party member who has cultivated an image as a pragmatic man of the people.

Both are deep institutionalists who have come up in diametrically opposed political systems and are now locked in a battle that Biden has cast as an existential test of democracy versus autocracy.

At one time, they referred to each other in glowing terms, but no more. Biden has called his onetime friend “a thug.” Xi recently called Biden “my old friend,” but his government’s statements of hostility toward the United States are unmistakable.

The hope of a detente, however frail, comes from a moment shortly after Barack Obama took office when the White House was eager to get a sense of Xi, who was a rising figure and presumptive leader of China but also an enigma.

“Xi was a bit of an unknown commodity — he had not served in the type of post that led to a lot of interaction with Americans,” said Ben Rhodes, who was Obama’s deputy national security adviser. “There was a real benefit in having somebody spend a lot of time with the guy to take his measure, get to know him and set up Obama’s capacity to hit the ground running with Xi when he became president.”

Biden had traveled to China only twice before, but he plunged into the task. He and Xi sat for tea and held several dinners, formal and informal. They held lengthy meetings in Beijing and traveled to Sichuan province to tour a centuries-old irrigation project. They visited a school, where Xi signed basketballs and Biden shot hoops (successfully scoring after a half-dozen tries).

Biden made news in Beijing when he slipped away for a lunch of pork buns, noodles and cucumbers at a small, family-run restaurant (it was known for its pig intestines, which Biden apparently skipped), joined by his granddaughter Naomi, who had studied Mandarin.

While Chinese leaders were criticized for being wealthy and distant, Biden dug into a meal that cost the equivalent of $12. The action won popular coverage on Chinese social media, though it may have discomfited his hosts with their more aloof style of leadership.

But Xi himself quickly showed signs of being a new, less formal kind of Chinese leader, if not quite an American-style politician.

“It was clear to me that Xi Jinping was trying to learn more from Biden as a peer, about how you do it, what is it like,” Russel said. “He was about to embark on this incredible project leading China. We had no idea at the time all of the plots and ambitions he had in the back of his mind, but he wanted to know more. This is not a person who had much experience dealing with the world.”

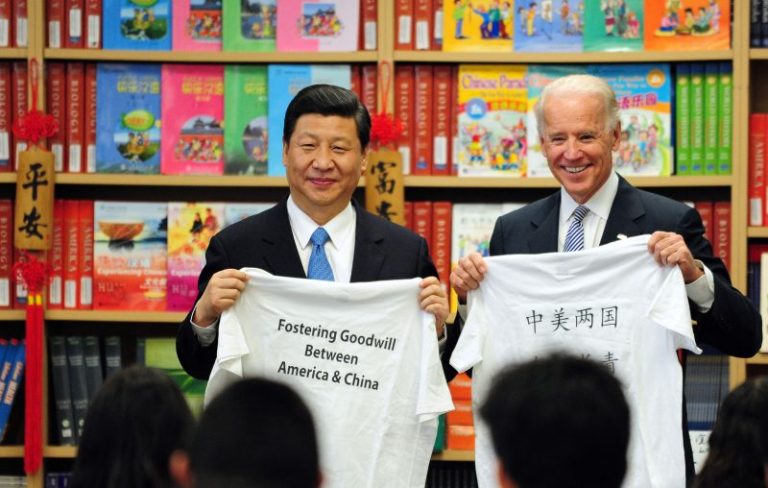

When Xi made a reciprocal visit to the United States six months later, Biden toasted him at a State Department luncheon and hosted him for dinner at the Naval Observatory, the vice president’s official residence. Later in the trip, Biden met Xi in Los Angeles, where they toured a school.

“What Biden’s trip helped reaffirm for us was that [Xi] is ambitious, he’s a larger personality, and we’re going to have to deal with a different type of Chinese leader,” Rhodes said. “The way Xi behaved on those trips, you could tell he was more of a politician than an apparatchik.”

Once Xi became president, Biden’s interactions were more limited as Obama took the primary role. He did travel to China in 2013 — accompanied by his son Hunter, who met with a Chinese business partner during the trip — and spent more than five hours with Xi.

Xi continued to confirm early impressions of his bolder, more personal style: Meeting with Obama in 2013 in Rancho Mirage, Calif., he broke out a bottle of hard liquor during a working dinner to toast his fellow president.

Like any number of stories Biden tells, those involving him and Xi have grown more elaborate over time. While they unquestionably spent large amounts of time together, Biden has dramatically overstated their engagements.

He has repeatedly claimed, for example, that they traveled 17,000 miles together in China and the United States. A White House official said Biden was referring to the total distance he traveled to attend the meetings — not necessarily their actual time together — but even that does not fully add up, according to The Washington Post’s Fact Checker.

Biden has also pegged the time they spent together when he was vice president at 24 or 25 hours, and as president, Biden has spent perhaps 10 more hours on the phone with Xi. Yet his estimates of their interactions have ranged far beyond that.

In March, he said the two had had “over 36 hours of private meetings.” A month later, he referred to it as “90-some hours of talking or meeting.” About four hours later, he remarked, “I think it’s now up to 70-some hours with Xi Jinping.”

Since then, he has cited their meetings on 12 occasions, often alternating between “76 hours” and “78 hours,” although he recently shaved off 10 hours and said they’d spent 68 hours together.

Biden also often says he has spent more time with Xi than any other leader has, something that is also probably a stretch. Obama spent significant time with Xi after Biden’s initial visits, and foreign policy analysts say that Russian President Vladimir Putin almost certainly has been with Xi more than any American president.

Xi is a primary character in one of the most frequent stories Biden tells. He has recounted it at a General Motors plant in Detroit; an infrastructure event in Rosemount, Minn.; a White House Hanukkah menorah-lighting ceremony; an Equal Pay Day event; a gathering of U.S. troops in Poland; and a Hispanic Heritage Month reception.

In the anecdote, Biden recalls being with Xi on the Tibetan Plateau when Xi asked him, “Can you define America for me?” Biden says he responded, “I can, in one word: possibilities.” Telling the story in July 2021, Biden elaborated, “Possibilities — it’s what America is built on. It’s one of the reasons why we’re viewed sometimes as being somewhat egotistical. We believe anything is possible in America.”

Aides who were with Biden say that they do not recall that precise exchange but that it would have been in keeping with the leaders’ open-ended conversations meant to probe each other’s world views. “They were unburdening themselves and trying to explain and convey what kind of a country are we, what do we believe?” Russel said.

Biden worked to draw out Xi, quoting William Butler Yeats or offering an aphorism he said came from his father: “The only thing worse than war is unintended war.”

But any bond has frayed over the years as China has taken on a new ambition and aggressiveness under Xi. Biden during his presidential campaign called him a “thug,” albeit “a smart guy.” He has said his counterpart does not have a democratic “bone in his body.”

And perhaps mindful of previous presidents who believed they had a rapport with Putin, Biden has dismissed the idea that he and Xi are buddies. “Let’s get something straight — we know each other well, we’re not old friends,” he said in June 2021. “It’s just pure business.”

But he has also referred, almost wistfully, to a time when the two engaged in a seemingly genuine effort to understand each other.

“We’ve spent an awful lot of time talking to one another, and I hope we can have a candid conversation tonight as well,” Biden said before a virtual meeting in 2021. “Maybe I should start more formally, although you and I have never been that formal with one another.”

“I’m very happy to see my old friend,” Xi responded.

The politics in both countries have changed radically since 2011, and the two superpowers are far more openly antagonistic.

“I think Xi Jinping believes his advantage on any American president is they’ll be gone before he is. He sits atop a system he has total control over,” Rhodes said. “He looks at a Joe Biden and knows, ‘I will be president of China after you are president of the United States.’ ”

Xi himself has changed, Rhodes added, which will force a recalibration from Biden.

“The Xi Jinping of 2022 is not the Xi Jinping of 2011,” Rhodes said. “That was a guy who was probably trying to ingratiate himself because he was a newcomer. Now he is a guy who thinks he’s the most powerful man in the world, even more powerful than the president of the United States. It’s the difference between the new kid on the block and the bully on the block.”

A senior administration official said White House aides expect the meeting to be a “substantive and in-depth conversation” between the two leaders but did not anticipate substantive progress on major issues.

Instead, the official said, White House officials view the meeting as an effort for Biden and Xi to understand each other’s priorities and establish a “floor” for the relationship to ensure lines of communication remain open at times of tension.

“I’m not willing to make any fundamental concessions,” Biden said during a news conference on Wednesday. “I’ve told him: I’m looking for competition — not conflict,” he added.

Leon Panetta, the former defense secretary who knows both men, compared their current interaction to “two boxers circling, really trying to weigh just exactly what the strengths and weaknesses are of the other side.”

He added, “I think deep down, both understand that in many ways, there has to be a better way for both countries to deal with one another rather than constantly threatening to destroy one another. In the personality for both of these leaders, there is a greater strain of wanting to see if there’s a way to accommodate the other. But who the hell knows — sometimes events can destroy the best of intentions.”