Donald Trump told his supporters that they ought to tune in next week for a special announcement — almost certainly some sort of formalization of his months-long winking about seeking the Republican presidential nomination in 2024. But Trump is not waiting for that announcement to begin taking shots at the man generally considered his most formidable opponent, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R).

Over at the social media platform Trump helped start, the former president has been on a tirade against DeSantis, very clearly out of frustration that DeSantis sailed to reelection on Tuesday while Trump-endorsed candidates were battered. So Trump is offering up context like “shouldn’t it be said that in 2020, I got 1.1 Million more votes in Florida than Ron D got this year, 5.7 Million to 4.6 Million?”

Most of this was just part of the ambient Trump noise that Americans generally tune out. But then there was another claim, a new one, that raised eyebrows. As part of a thread claiming credit for nearly every aspect of DeSantis’s political career (not completely unfairly), Trump brought up the aftermath of the 2018 election in Florida that DeSantis narrowly won.

“After the Race, when votes were being stolen by the corrupt Election process in Broward County, and Ron was going down ten thousand votes a day, along with now-Senator Rick Scott,” Trump wrote, “I sent in the FBI and the U.S. Attorneys, and the ballot theft immediately ended, just prior to them running out of the votes necessary to win. I stopped his Election from being stolen.…”

This is a really remarkable claim, that as president he leveraged the Justice Department to intervene in an election. It is also almost certainly false.

It’s useful to remember what happened that year. In an echo of the midterm elections just ended, 2018 was a remarkably good year for Democrats — except for Florida. There, Democratic advantages in the gubernatorial and Senate races evaporated, leading to narrow Republican victories. DeSantis won by about 30,000 votes; incumbent Gov. Rick Scott won election to the Senate by about 10,000.

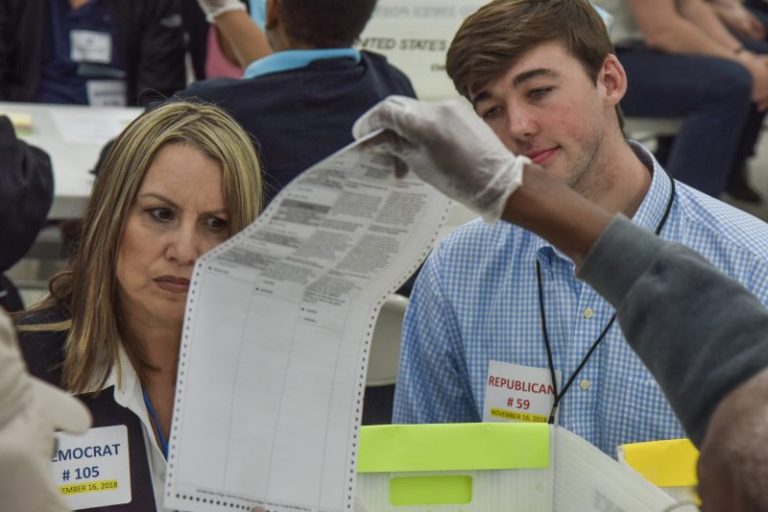

Those margins were close enough that attention turned to the counting of mail ballots in the days after the election, a process that is by now deeply familiar to political observers. So was the context in which that counting took place: Scott alleged that the slow process of counting votes in Democratic-heavy counties like Broward offered the opportunity for illegal ballots to be injected. There was no actual evidence of this; he and his allies insisted that ballots were appearing out of nowhere to be included, which wasn’t true. But it was a way to cast doubt on the vote and, potentially, to shut down a vote count that had consistently eroded his advantage after Election Day.

This is what Trump appears to be referring to. But the timeline of what happened makes clear that none of this had anything to do with DeSantis.

Scott first made his allegations about fraudulent voting in a news conference on the evening of Nov. 8, 2018. This was the first moment at which this idea that the vote count was suspicious was introduced (beyond rumblings for a few hours prior). But notice that it was Scott who was making these allegations, not DeSantis.

There’s a good reason for this: DeSantis’s race had already been called! The Associated Press declared DeSantis the winner of the gubernatorial race nearly two days before.

BREAKING: Republican Ron DeSantis wins election for governor in Florida. #APracecall at 11:27 p.m. EST. @AP election coverage: https://t.co/miEWlbTVZW #Election2018 #FLelection

— AP Politics (@AP_Politics) November 7, 2018

Vote counting did continue to reduce DeSantis’s lead, but there were not enough outstanding votes to potentially alter the outcome. So the call was made, and there was no question whether he would have “the votes necessary to win,” as Trump put it.

You may also recall that a potentially related incident occurred at the same time: Trump’s first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, resigned his position. Was this a function of resistance to pressure to influence the outcome in Florida?

Probably not. Sessions’s resignation was announced on the afternoon of Nov. 7, 2018, before there was any public question about the vote counting in Florida. What’s more, there had been months of animosity between Sessions and Trump over the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election. There was plenty of reason to think that Trump wanted Sessions gone unrelated to any purported FBI pressure.

The question then becomes: Did Trump ask the FBI to shut down the vote count in Florida on Scott’s behalf?

There’s no evidence that he did. By all accounts, the process of counting ballots in the targeted counties continued slowly — and not without contentiousness — until all of the votes were tallied. The AP called the race for Scott on Nov. 20. An investigation later determined that a number of problems had surrounded the counting in Broward County, but that none of them affected the outcome of any races. There was no evidence of rampant illegal voting.

That, not some belated admission from Trump, will likely be the lasting legacy of the 2018 contest in Florida. Scott alleged illegal voting, without evidence — a claim certainly aimed at putting pressure on Democratic counties as the vote tallying was underway. Trump elevated those claims. Conservative media seized upon them. Pressure ensued.

Republican protest crowd doubles to about 60. Chant of lock her up breaks out pic.twitter.com/PfBHkbokha

— Alex Harris (@harrisalexc) November 9, 2018

In other words, it was a preview of what was to follow two years later. Which, of course, is a point in favor of the theory that Trump’s claims this week were baseless and simply aimed at taking credit for DeSantis’s 2018 win. We know that Trump worked very hard to get the FBI to intervene in the 2020 election results, but that no intervention followed.

There’s no reason to think that the Bureau was influenced more successfully two years prior.