“The AP is not a news organization. It is a propaganda factory. American Pravda should not be allowed to ‘call’ elections. That should be up to the Department of State in each state, in a timely and transparent manner.”

— Christina Pushaw, rapid response director, Ron DeSantis campaign, in a tweet, Oct. 27

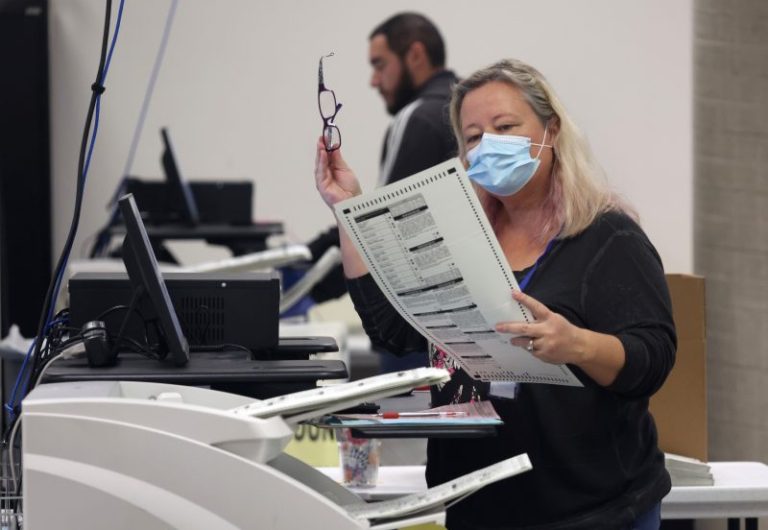

The Fox affiliate in Phoenix last month accidentally aired during a live broadcast a test election result from the Associated Press showing the Democratic candidate for governor winning that state’s hard-fought election. The incident drew outrage from Republicans on social media, including the tweet above, although the station quickly acknowledged the mistake: “This graphic was never meant to go on air — the numbers were only part of a test. The station has taken steps to make sure this cannot happen again.”

Pushaw’s tweet misrepresents what happens. In fact, the AP reports election results that are provided by state and local officials, using its vast network of employees and affiliates. At a certain point, based on how many votes remain to be counted, AP may conclude that a candidate is the winner because no other candidate can catch up. That’s newsworthy. But the AP does not engage in speculation or projections. And no election is official until all of the votes are counted and the election results are certified.

The AP’s singular place in conveying U.S. election results dates back to the mid-19th century. Here’s an explanation about how, and why, its role emerged.

The AP was created in 1846 largely as a result of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel Morse a couple years earlier. Historian David Walker Howe, in his Pulitzer-Prize winning “What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848,” traces the formation of mass political parties to this revolution in communications. At the time, newspapers were organs of political parties. They “quickly enlisted the telegraph in their quest to gather and distribute information,” he wrote.

But there was a problem. The new instrument could handle only a certain number of messages at a time, creating a logjam in the distribution of news, Howe said. Six newspapers in New York in 1848 joined to form the AP to ease the congestion — but also because they feared competition from Morse’s landline telegraph network, according to Richard R. John, a professor of history and communications at Columbia University.

Meanwhile, in 1845, Congress passed a law that for the first time set a national Election Day, replacing a previous 34-day window.

Thus the first presidential election that took place on a single day was the 1848 contest between Gen. Zachary Taylor, a Whig, Sen. Lewis Cass, a Democrat, and a former Democratic president, Martin Van Buren, running on a third-party ticket. The AP was in place to report on the news, spending the then-astronomical sum of $1,000 on telegraph tolls to pool information on election results from local newspapers in the 30 states that voted then.

According to Howe, “counting the votes proceeded so slowly it took a week to reveal the outcome” — that Taylor had defeated Cass, 163 electoral votes to 127.

The AP reported the outcome but “was not formed to ‘call’ elections,” John said, adding that he has seen no evidence the AP “called” either the 1848 or the 1852 election — “or that anyone would have paid attention if it had.” But from that point, the news organization took on the responsibility of collecting information about election results — a 2007 history of the AP recounts how the Pony Express was used to collect California’s results in 1860 so it could be dispatched via telegraph — and announcing who had won.

To this day, the United States has no central election authority, with elections run by more than 8,000 local governments. That has kept the AP central to the reporting of news on elections.

“We have 4,000 stringers reporting the vote, in addition to 1,000 vote entry clerks, and AP’s regular staff,” said Lauren Easton, AP’s vice president for communications. “It’s a significant investment.”

According to the AP, in the 2020 election, the news organization declared the winners in more than 7,000 races. “AP does not make projections or name apparent or likely winners. If our race callers cannot definitively say a candidate has won, we do not engage in speculation,” the AP’s website says. “AP did not call the closely contested race in 2000 between George W. Bush and Al Gore — we stood behind our assessment that the margin in Florida made it too close to say who won.”

In 2020, the AP says it was 99.9 percent accurate in all of its race calls — and perfect in declaring presidential and congressional races in each state. The AP no longer uses exit polls to assist in making its election decisions, believing interviewing voters at polling places no longer yields a complete picture of the electorate. Instead, it supplements the vote count with a massive survey of registered voters taken in the days before polls close.

David Greenberg, a Rutgers University history professor, said that in many ways, the United States is moving back to a political system in place when the AP began tracking election results nearly 175 years ago. Some news organizations have become more partisan and closely associated with political parties — and, with the advent of mail and absentee voting, the vote count is taking longer to yield a winner.

“There was not an expectation that the winner of the election would be quickly known until the 20th century,” Greenberg said. “We now may have to live with the fact that results are going come in after a week or two.”

(About our rating scale)

Send us facts to check by filling out this form

Sign up for The Fact Checker weekly newsletter

The Fact Checker is a verified signatory to the International Fact-Checking Network code of principles