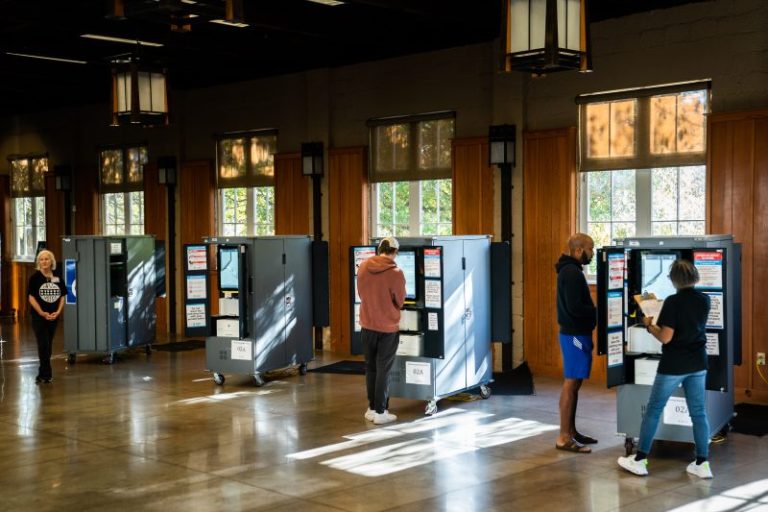

The United States on Tuesday began an expected marathon of voting — and vote counting — as an intense new era of partisan scrutiny of elections and their outcomes promised to test the resilience of American democracy, and possibly require days to determine control of Congress.

By midday in Washington, polls had opened across most of the country, marking the first nationwide Election Day in two years, as well as the two-year mark since Donald Trump severely undermined confidence in the U.S. democratic process, claiming without proof that he lost in 2020 only because of a rigged election.

Thousands of local and state election officials were bracing for the democracy stress test to begin in earnest Tuesday night, in some cases erecting barriers and putting police on standby for when vote counting begins. But already, there were signs of tension.

Get ready to vote with our democracy toolkit

End of carousel

Election deniers had begun seizing on an isolated voting glitch in Arizona and a likely delay in vote-counting in Pennsylvania to spin viral theories of vote manipulation. Complaints filed by voters showed that efforts by members of far-right groups to insert themselves as poll watchers in some precincts might be causing confrontations. Simultaneously, officials in Republican-controlled states were also chafing at stepped-up federal oversight of the election, with authorities in Florida and Missouri saying they would block federal monitors from entering polling places to ensure compliance with federal civil rights laws.

In a letter to Justice Department officials released Tuesday morning, Brad McVay, an attorney for Florida’s Department of State, wrote that federal attorneys were “not permitted” in polling places in the state and “could potentially undermine confidence in the election.” Federal monitors have regularly visited state polling places for decades on Election Day, and, in Florida, as recently as 2020, observers said, but many did not go indoors that year because of covid.

The pushback followed a similar protest by Missouri Secretary of State John R. Ashcroft (R), who told The Washington Post on Monday that federal monitors would not be welcome there as they would “bully a local election authority” and could “intimidate and suppress the vote.”

A spokeswoman for the Justice Department, which announced Monday that it would dispatch monitors to 64 jurisdictions, or almost 50 percent more places than during the 2020 election, said monitors in Florida and Missouri were remaining outside polling places. The Justice Department urged any complaints related to disruption at polling places to be reported immediately to election officials, and any threats of violence or intimidation to be reported to police.

In Texas, alleged racial intimidation at a polling place was reported just before polls opened.

Late Monday, a federal judge held an emergency hearing on a suit by the Beaumont chapter of the NAACP, alleging that White election officials harassed Black voters during early voting in the East Texas city.

According to the suit, White poll workers “repeatedly asked in aggressive tones only Black voters and not White voters to recite, out loud within the earshot of other voters, poll workers, and poll watchers, their addresses, even when the voter was already checked in.”

The suit claimed that White poll workers and poll watchers followed Black voters and Black voter assistants around polling places and stood behind a Black voter while they voted.

The lawsuit requested that a federal judge declare election workers’ treatment of Black voters an unconstitutional violation of the federal Voting Rights Act and block them from engaging in similar behavior on Election Day.

In Georgia, election officials in Fulton County said Monday that a woman and her son were asked not to serve after fellow election volunteers notified the county of Facebook posts showing the family partaking in the mob that stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

State officials called it a minor issue. Overall, “it’s been a spectacularly boring morning so far,” said Gabriel Sterling, the state’s interim deputy secretary of state. He noted that the longest wait to vote Tuesday morning had been 12 minutes, and the average across Georgia had been two minutes, with most polling locations having no wait.

Susannah Goodman, director of election security at Common Cause, which is monitoring polling issues nationwide, expressed similar relief hours into the vote.

Goodman said that in some precincts, some machines or scanners have not worked properly, but problems have not prevented people from voting. “What we’re seeing are things that we usually see on Election Day,” she said. “These are things we see in every election cycle.”

Goodman said the most significant problem the organization saw Tuesday morning was around Detroit, where there were problems with checking in Wayne County voters, and election officials had to switch to paper poll books, causing delays. The Michigan Secretary of State’s Office said that the problem was resolved by noon and that voting was proceeding smoothly, with heavy turnout statewide.

A polling location at a school in Kenner, La., had to be moved Tuesday after a bomb threat was called in to a Jefferson Parish campus. But it was unclear whether the bomb threat, the second in the past week, was related to voting, authorities said.

In Arizona, where some small groups had loitered around ballot drop-off locations ahead of Tuesday, claiming to be patrolling for election fraud, concerns about intimidation had pushed some voters to cast ballots in person.

Matt Kroski said he usually votes early, but after seeing reports of the armed observers, he decided to make a statement by casting his ballot in person on Election Day. “It’s just voter intimidation,” said Kroski, 43, who lives in a neighborhood north of downtown Phoenix.

“Emotionally, it made me fearful, because it’s our one chance to make our voice heard.” said Kroski, one of the first to arrive at the polling location inside a Greek Orthodox church near the city’s Biltmore area. He expressed a cautious faith in the system of democracy but said he was unsure what would happen if Republicans took complete control of the state and its election administration.

Problems with machines at some voting locations in Maricopa County, home to more than half of Arizona’s voters, became grist for prominent right-wing voices who deny the legitimacy of the 2020 election to claim without evidence that Tuesday’s vote was also fraudulent.

Tabulators at about 20 percent of the 223 voting locations in the county were experiencing problems, county officials told The Post. Elections officials were fixing the problems and advised voters to wait for tabulators to come back online, go to another voting location or drop ballots in secure slots. Ballots dropped in the slots are counted either at the end of the day or in the coming days at the county’s tabulation center in downtown Phoenix, said Megan Gilbertson, spokeswoman for the county’s election department.

County officials stressed that no one was being prevented from voting and that no one’s ballot had been mishandled. They have said for weeks that ballot counting could take as many as 12 days.

Jesse Littlewood, who analyzes disinformation for Common Cause, said that as of midday Tuesday, social media traffic seemed to be working to amplify reports of routine problems and then use them as “part of the narrative that says these are somehow intentional … to undermine people’s faith in the integrity of the election process.”

Littlewood said there is a “bubbling-up” of the existing false claim that “if election results are not counted and confirmed on the night of the election, that it is somehow fraudulent.”

In Philadelphia, election officials warned hours ahead of time that they may not be able to complete ballot counting Tuesday night, blaming Republicans for the possible delay.

Under pressure from a Republican lawsuit, city officials said they would interrupt ballot counting to make sure each voter who returned a mail-in ballot had not been allowed to also vote in person, a process known as “poll book reconciliation.”

“I want to make very clear that when there are conversations that occur later this evening about whether or not Philadelphia has counted all of their ballots, that the reasons some ballots will not be counted is because Republican attorneys targeted Philadelphia — and only Philadelphia — in trying to force us to do a procedure that no other county does,” Philadelphia City Commissioner Seth Bluestein, a Republican, said Tuesday at a public meeting of the election board.

The disruption to the city’s count is the latest sign that partisan litigation will continue to impact Tuesday’s vote in Pennsylvania and beyond. Republican officials and candidates in at least three battleground states have been pushing to disqualify thousands of mail ballots. Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court has already sided with Republicans, ruling that election officials should not count ballots on which the voter neglected to put a date on the outer envelope — even in cases when the ballots arrive before Election Day. Thousands of ballots have been set aside as a result, enough to swing a close race.

There were also more troubling signs ahead for Tuesday night. Some increasingly viral social media posts were carrying unfounded claims of Republican voters being barred from polls, and some tweets spun minor, early-morning mechanical problems with vote tabulators into elaborate claims of systematic fraud.

Users on the pro-Trump extremist forum “The Donald” urged armed intervention at ballot-counting centers in Georgia, advising, “If it gets violent, shoot first.”

In a statement Tuesday, Idaho’s chief elections official, Lawerence Denney, said election workers were seeing many unfounded claims and he urged voters to only trust official channels.

“Idaho’s elections are run by 44 elected county clerks with oversight by the secretary of state,” Denney said. “It’s only logical, then, that Idahoans’ trusted source of information on elections should start in the same place — with their local clerk. The more we can keep the disinformation from spreading by checking details at the source, the better election we can run for Idaho.”

Emma Brown, Matt Brown, Amy Gardner, Tom Hamburger, Rosalind S. Helderman, Molly Hennessy-Fiske, Yvonne Wingett Sanchez, Isaac Stanley-Becker, Perry Stein, Reis Thebault and Carissa Wolf contributed to this report. Matt Brown reported from Georgia, Hamburger from Michigan, Hennessy-Fiske from Texas, Sanchez and Thebault from Arizona, and Wolf from Idaho.