This tweet from FiveThirtyEight’s Nathaniel Rakich was intended mostly as a joke.

Congratulations to Republicans on their victory in the 2022 midterms!

— Nathaniel Rakich (@baseballot) November 6, 2020

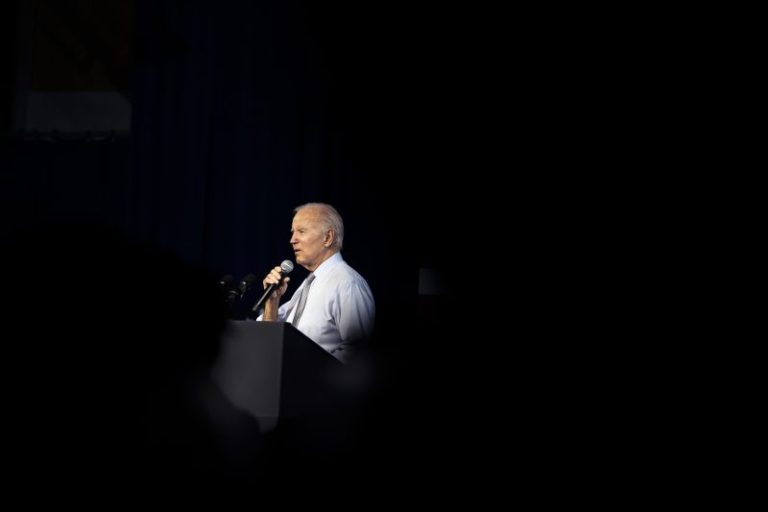

Note the date. He posted that on Nov. 6, 2020, the day Donald Trump’s reelection loss became obvious but even before it was formalized. Back then, more than two years ago, Rakich was making a sort-of-tongue-in-cheek prediction: because first-term presidents almost always see their party lose seats in the first midterm election of their terms, a victory by Joe Biden in 2020 augured a loss by Democrats in 2022.

This could certainly have been wrong. Biden could have been unusually popular and the recovery from the pandemic unusually robust. Lots of things can happen over two years’ time that upend expectations. But this particular expectation, that Republicans will do better in the midterms than Democrats, seems almost inevitable as the final votes are counted.

Raising a question that candidates and consultants and many other observers would rather not ask: To what extent was the outcome of the midterms baked in for most of the past two years?

It is the afternoon of Nov. 8, 2022, as I write, meaning we don’t yet know what the midterms will bring. But we can look at what has happened in past midterms to get a sense.

FiveThirtyEight has historic approval rating averages that allow us to compare apples to apples here — or at least, as close to apples-to-apples as we’re likely to get. If we look at the last 100 days preceding the first midterm election of a new president’s term in office (excluding those who took office under unusual circumstances) we see a few patterns emerge.

One is that there is much less variation in the average now than there used to be. This is largely a function of polarization: Partisans love presidents from their party and hate presidents from the opposing party. We also see that the president whose pre-midterm approval pattern Biden best matches is Ronald Reagan’s, something that the president might find heartening as he considers a 2024 bid.

But what we mostly see is that the level of support for a president’s party in the midterm (indicated with a horizontal dotted line) doesn’t correlate very well with approval. After all, the period before 1994 was one in which Democrats consistently held large majorities in the House even if they didn’t in the Senate or if Republicans controlled the White House. That’s a main reason that the national Democratic House vote in that top row (that is, in 1962 and 1978) is above 50 percent, while the Republican vote (in 1954 and 1970) is below 50 percent — even though Dwight D. Eisenhower was much more popular on Election Day in 1954 than Jimmy Carter was in 1976.

So let’s instead consider the change in seats held by the president’s party in each midterm. Here we see a much sharper correlation.

In only one election — 2002 — did the president’s party gain seats in the midterm. That was largely a function of George W. Bush’s popularity, boosted in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. In each of the other nine elections since 1954, the president’s party has lost seats. And the less popular the president, the bigger the loss.

The trend line displayed there shows how approval correlates to seat loss or gain, but it is not predictive. For example, it’s not the case that because Biden’s approval average is just north of 40 percent (shown with the horizontal blue dotted line), we can expect Democrats to lose more than 60 seats in the House. Other factors come into play, including how many seats have been drawn to be safe for one party or the other.

In the two previous elections in which presidents have been about as unpopular as Biden, 1982 and 2018, their party lost dozens of seats. Democrats’ losing even one dozen this year means Republican control of the House. In other words, looking only at Biden’s approval, we would expect the GOP victory that Rakich jokingly predicted. Even if Biden’s approval were higher, in fact, his party’s narrow House majority would mean that Republicans probably would gain, given the precedent illustrated above.

There will be a lot of discussion over the next few weeks about what happened and why. Candidates will insist it was their specific qualities that led to their victories; consultants will insist it was their own wily tactics. This is what happens.

The reality is that certain patterns occur in politics over and over again. One of them would suggest that Democrats are in for a bad night Tuesday — as could have been predicted two years ago.