Cutting housing subsidies for the poor by 33 percent as soaring rents drive a national affordability crisis. Forcing more than 1 million women and children onto the waitlist of a nutritional assistance program for poor mothers with young children. Reducing federal spending on home heating assistance for low-income families by more than 70 percent with energy prices high heading into the winter months.

The looming government shutdown: What to know

End of carousel

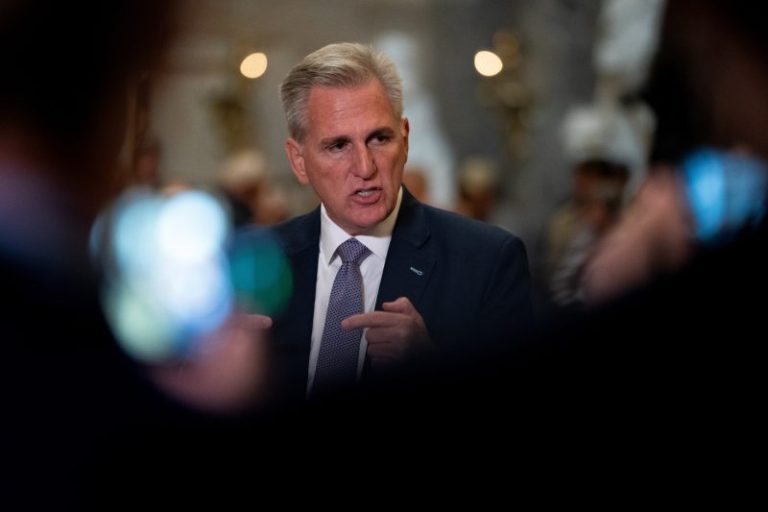

With days left before the government shuts down, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) has embraced steep reductions to the U.S. safety net in an attempt to appease far-right Republican demands for lower spending. If McCarthy can win over conservatives and pass legislation funding the government, Republicans hope to have greater leverage in negotiations with the Democratic-controlled Senate and White House.

But far-right votes have remained elusive, leading McCarthy to propose ever larger and still evolving spending cuts. “The level of reductions in the existing House resolution set us back significantly on issues that government should be funding for the benefit of this country,” said G. William Hoagland, senior vice president of the Bipartisan Policy Center, a think tank in Washington.

“Their proposals were already almost an impossibility before. But if they go even further, as they are now discussing, I don’t see how we can address many of the major issues the nation is trying to address,” Hoagland added. The estimated cuts to housing, nutrition assistance and home heating aid come from the Center for American Progress, a center-left think tank.

Rep. Garret Graves (R-La.), a top McCarthy lieutenant, told reporters over the weekend that the House leadership plans to cut spending on “discretionary” programs, a category that excludes programs such as Social Security and Medicare, by roughly 27 percent, except for the military budget and spending on veterans affairs.

That appears to translate into taking more than $150 billion per year out of the part of the budget that funds child care, education subsidies, medical research and hundreds of additional federal operations. The “bottom line is we’re singularly focused right now on achieving our conservative objectives,” Graves said. Trying to court the votes of far-right lawmakers, he added that these “huge savings” were being proposed “despite the fact that you’ve had record inflation under this administration.”

McCarthy, for his part, has emphasized that he is focused on approving government funding legislation with the narrow Republican majority, rather than trying to craft a bipartisan compromise that draws Democratic support. Hard-right lawmakers have warned that if McCarthy relies on Democratic votes to pass any fiscal bill, they would move swiftly to force him from the speakership.

“I believe we have a majority here, and we can work together to solve this,” McCarthy told reporters. “This is the same place you were all asking me during the debt ceiling. So you know what, it might take us a little longer. But this is important. We want to make sure that we can end the wasteful spending that the Democrats have put forth.”

House Republicans have not unified, at least so far, on a single spending plan, which complicates attempts to characterize the party’s position that is changing by the day. House lawmakers plan to try to move ahead Tuesday with a package of spending bills that would cover the full 2024 fiscal year for four swaths of the government.

But even if those bills were approved by the Senate, which they will not be, much of the government would still shut down because federal operations are funded by 12 different bills. Hard-right holdouts blocked action on one of those bills last week.

Lawmakers in both chambers are contemplating plans for a short-term extension to active spending laws, which otherwise will expire at 12:01 a.m. Sunday, shutting down the government. House conservatives have objected to any short-term bill without deep spending cuts, and some object to any short-term bill at all.

As McCarthy has seen his efforts to fund the government derailed by repeated revolts, he has toyed with larger spending cuts in hopes of passing something through the chamber to minimize the extent to which Republicans are blamed for a potential shutdown.

In June, President Biden and McCarthy agreed to avert a debt limit crisis with a deal that kept government funding at nearly flat levels for the next fiscal year. That amounted to a spending cut when accounting for inflation. Lawmakers also agreed to pull back tens of billions of dollars that Democrats had approved for expanding the Internal Revenue Service.

However, conservatives have regarded the spending agreement as a starting point for negotiations, and they spent the summer pushing for much lower funding levels. The hard-right lawmakers angry about the debt ceiling deal froze the House for a week in June by blocking procedural votes on noncontroversial legislation.

McCarthy conceded to their demands and directed the House Appropriations Committee to prepare the 12 spending bills that fund the government for the 2024 fiscal year at the 2022 spending levels, well below what Biden and McCarthy had agreed on.

And despite protests from the White House, Republicans on the House Appropriations Committee advanced legislation in July that would cut spending by roughly 9.5 percent on average, according to Bobby Kogan, senior director of federal budget policy at the Center for American Progress.

Many federal programs would have seen much more dramatic reductions. The proposals would bring spending on these domestic programs to their lowest point as a share of the economy in at least 60 years, Kogan said. (Democrats have characterized these plans as a 23 percent cut, when taking into account proposed spending reductions to the Inflation Reduction Act and other programs.)

The plan from Republican appropriators called for a roughly 80 percent cut to funding for public schools that serve high concentrations of students in poverty, according to the Center for American Progress. It would have also cut by at least half a fruit and vegetable benefit for poor pregnant mothers, which serves roughly 5 million people. It would have slashed the budget for the office responsible for administering Social Security benefits to tens of millions of Americans, while advancing major cuts to the National Institutes of Health, Head Start and preschool grants.

“It is bad news for kids and lower-income households, undoubtedly,” said Michelle Dallafior, the senior vice president of budget and tax for First Focus on Children an advocacy group. The maximum amounts of Pell Grants for low-income students would be frozen, the National Labor Relations Board would see its budget cut by a third, and affordable housing grants would be cut by about two-thirds, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Yet a small handful of far-right conservatives, including Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.) and Rep. Andy Biggs (R-Ariz.), has rejected these cuts as insufficient. Many of the demands from the House Freedom Caucus and other far-right lawmakers stem from promises by McCarthy while he ran for speaker in January, when House Republicans failed multiple times to select a leader.

Since House lawmakers return from their August break two weeks ago, McCarthy has had to pull consideration of the procedural vote that would have greenlit debate on the bill to fund the military multiple times. That failure shook some House lawmakers into recognizing that they needed a backup plan to fund the government in the short term as they barreled closer to a shutdown.

Six Republican members from two different factions, three from the pragmatic Main Street Caucus and three from the hard-right Freedom Caucus, met for several days before announcing a deal on a stopgap measure last week. That would have funded the government for 30 days, cutting every department except the military and veterans programs by 8 percent. It included most of a Republican-approved border security bill.

The White House said that plan would mean 300,000 households, including 20,000 veterans, would lose housing support, 6.6 million students would see their Pell Grants cut, 60,000 seniors would lose help from services like Meals on Wheels and 2.1 million women would be waitlisted due to the cuts to the program for poor women who are pregnant or mothers. And yet again even these cuts, despite being blessed by several Freedom Caucus leaders, were also rejected by the smaller faction of hard-right House conservatives, who panned the measure and argued it still spent too much money.

The impasse has forced McCarthy into a legislative bind with only days to spare before a shutdown that many Republicans believe will bring a political backlash to their party. House Republican officials have discussed another $60 billion in spending cuts, but it is unclear if such a measure would prove sufficient to appease the remaining conservative holdouts.

“Speaker McCarthy is proposing increasingly deep cuts to some parts of the social safety net and many other critical government functions in an attempt to appease extreme members of his caucus,” Kogan said. “This would increase suffering among some of the most vulnerable Americans.”