When police pulled over the car in Winterville, N.C., after a Walmart run in October 2018, Dijon Sharpe was wary — and ready. From the passenger seat, he opened Facebook Live and started to speak directly to anyone watching.

As one officer ran the driver’s license, another grabbed at Sharpe’s phone and issued a warning.

“Facebook Live, we’re not gonna have, because that lets everybody on Facebook know we’re out here,” the officer said. He then said he would make an exception, but that “in the future, if you want to Facebook Live, your phone’s going to be taken from you, and if you don’t want to give up your phone, you’ll go to jail.”

Sharpe expressed skepticism as he continued to record.

“Is that a law?” he asked. “That’s not a law.”

Whether it’s legal is now before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

“This case is important; it’s going to affect thousands of thousands” of people, Sharpe’s attorney, Andrew Tutt, said at oral argument last month. “This case has important consequences for every police-citizen interaction in this circuit.”

No circuit court has yet ruled on whether passengers in traffic stops can be blocked from recording police or on whether live-streaming is different from merely recording, and the Fourth Circuit has not ruled on the right to record at all.

“It is not a clean case in terms of precedent, and that’s what makes it complex,” said Clay Calvert, a law and communications professor at the University of Florida. “New technologies kind of push the boundaries of things — this is how law evolves.”

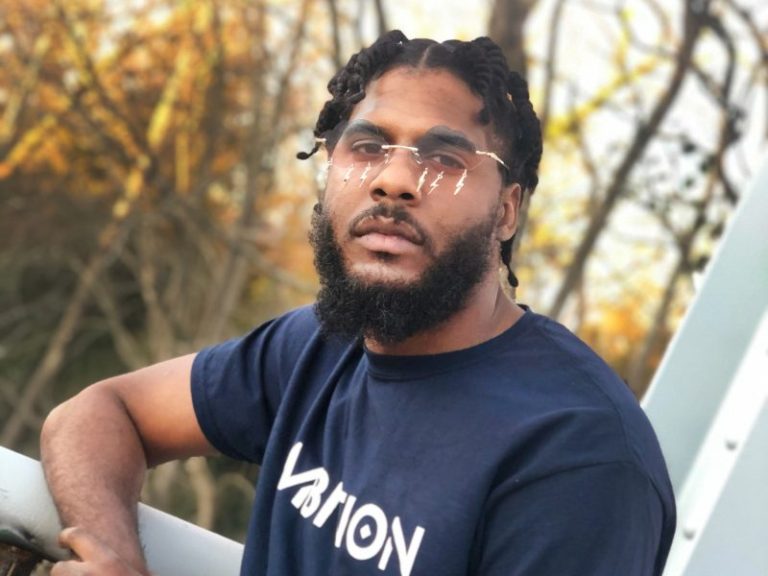

Sharpe, now 27, said he preferred live-streaming because it was clear to viewers that the footage wasn’t edited or out-of-date: “This isn’t prerecorded, this didn’t happen last year … this is happening right now, I’m not just making it up.” Live-streaming on Facebook also creates an immediate record that prevents police from seizing a phone and deleting footage before it’s released, he noted: “It’s just more secure for the community or the individual.”

At the time of the stop, Sharpe’s cousin was still in prison for a murder committed over two decades earlier, despite a key witness recanting her testimony almost immediately after trial. (Dontae Sharpe, the cousin, was released in 2019, after 24 years in prison, and formally pardoned in 2021 for his wrongful conviction.) Since getting involved in efforts to free Dontae, Dijon says his encounters with police grew increasingly hostile, culminating in his being Tasered and beaten by police officers in 2017. With no video to support his version of events, he says, he was forced in court to apologize to them.

“I made it my business to always just record traffic stops, especially when I’m involved,” he said.

He also thought the Winterville stop was suspect — the driver was accused of running a stop sign, which Sharpe said in the video was not true.

Sharpe said he viewed the argument that his live stream would endanger the officers by drawing more people to the area as ridiculous.

“Everyone in the world knows that there are cops out in the world,” he said. “I just knew that he was fishing, fishing for a reason.”

But a district court judge in North Carolina found that the safety concern was compelling enough to protect the town and its police officers from the lawsuit.

“Contemporaneous messaging applications allow the individual recording, and those watching, to know the location of the interaction and to comment on and discuss in real-time the interaction,” the judge wrote, which is “distinct” from recording but not live-streaming.

Seven federal appellate courts have affirmed that there is a First Amendment right to film the police. But all said there can be “reasonable” restrictions on that right, and the U.S. Supreme Court has not clarified what counts.

That ambiguity can be exploited by authorities, Calvert said: “The reasonableness, what’s a reasonable limitation, is a slippery concept.”

The National Press Photographers Association wrote an amicus brief in support of Sharpe, saying, “If anything, the immediacy offered by livestreaming weighs in favor of its First Amendment protection, because the technology offers a uniquely unfiltered view into events as they unfold, and serves to protect the material from being deleted, modified, or otherwise suppressed.”

At oral argument, judges seemed less interested in the First Amendment implications than the Fourth Amendment — which guards against unreasonable searches and seizures.

“It seemed to me that the issue we have in this case is what may the police do to persons that are subject to a … a traffic stop,” Judge Paul V. Niemeyer said. “What rights does an officer have to maintain control of the circumstances?”

Judge Julius N. Richardson agreed, noting that passengers at a traffic stop could be asked to get out of the car or to keep their hands visible.

Tutt argued that was irrelevant, because the officers did not suggest they needed to restrain Sharpe or see his hands — only to stop him from live-streaming: “We think that this falls well within the kinds of things that are off-limits.”

But Lenese Herbert, an expert in policing and the constitution at Howard University School of Law, said the Supreme Court has given law enforcement great leeway when the First and Fourth amendments intersect.

“You would think combined they would create a super amendment. They have not,” she said. Instead, police can then argue that their actions were not about speech but controlling a possible crime scene and potential criminals: “Officers basically get to subvert the First Amendment by couching it in Fourth Amendment terms, and allow the court to undermine First Amendment rights.”

The Supreme Court has recognized traffic stops as particularly dangerous for police. (According to preliminary data from the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, three officers died while conducting traffic stops last year; a recent study put an officer’s chance of being killed during a routine stop at 1 in 6.5 million and of serious assault at 1 in 361,111).

“There are no special protections for passengers” in a car, Herbert said. “The Supreme Court has made it very clear if you’re in a vehicle, you’ve got a Fourth Amendment right, but it’s a lesser right.”

But she did say Sharpe had a good case that the officer should not have grabbed his device — “If the officer sort of goes into the phone, looks in the phone, that the Supreme Court has said is a search that requires a warrant.”

Two appellate courts have found a First Amendment right to record traffic stops, but in neither was the person filming in the stopped car. Even if the Fourth Circuit rules for Sharpe, it could also find that the officers and town are immune from suit because the right to record in this situation wasn’t clearly established. The district court judge found that, given the legal novelty of the scenario, they were.

“There isn’t a lot of case law, not because this is something that doesn’t come up but because it’s thought to be so clear that it’s constitutional and protected that it doesn’t get litigated,” Tutt said in an interview. “Sometimes the law doesn’t develop because the overwhelming majority of police officers are following the law.”