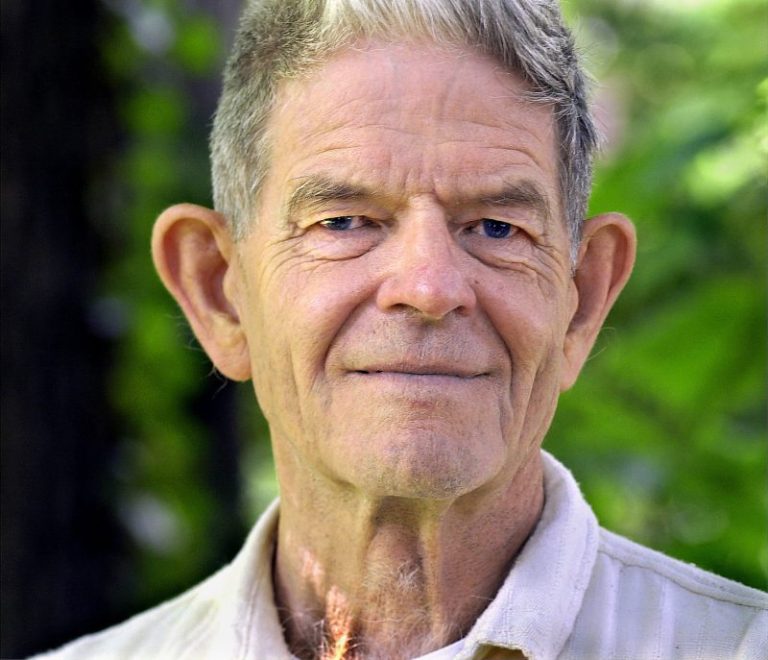

Staughton Lynd, a radical-leftist historian, civil rights organizer and antiwar activist who gained national prominence in 1965 when he traveled to Hanoi and denounced the Vietnam War as “immoral, illegal and antidemocratic,” then became a labor lawyer after saying he was “blacklisted” from his university teaching career, died Nov. 17 at a hospital in Warren, Ohio. He was 92.

The cause was multiple organ failure, said his biographer Carl Mirra, an associate professor and director of liberal studies at Adelphi University in Garden City, N.Y.

Mr. Lynd, a self-styled Marxist, pacifist and existentialist — but not a communist — was “one of the visible saints of the modern American left,” a writer for the Nation magazine observed in 1997, describing him as a notable figure long after the 1960s. “His example, at once political, intellectual and even spiritual, continues to inspire.”

As a radical historian — he taught at Spelman College, a historically Black school for women in Atlanta, and later at Yale University — Mr. Lynd employed, he once wrote, “nonviolence when possible, civil disobedience if necessary, but direct personal action in all cases.”

In 1964, Mr. Lynd traveled to Mississippi for Freedom Summer, overseeing the creation of schools to address inequities in Black education. The next year, he participated in several momentous antiwar protests, including the March on Washington to End the War in Vietnam, which was organized by the Students for a Democratic Society and drew more than 20,000 people. In another protest, he and fellow activists Bob Moses and David Dellinger were splashed by counterprotesters with red paint.

As Mr. Lynd’s stature in the antiwar movement grew, so did his boldness. In 1965, accompanied by Herbert Aptheker, a Communist Party member and prominent Marxist historian, and Tom Hayden, leader of Students for a Democratic Society, he went on an unauthorized “fact-finding” mission to Hanoi and met with North Vietnamese officials.

The 10-day trip, seen by communist news agencies as a propaganda coup, angered officials in Washington but raised Mr. Lynd’s status as one of the foremost intellectuals against the war. In 1966, he appeared on the TV talk show “Firing Line,” hosted by conservative commentator William F. Buckley Jr.

“Our purpose in going, mine at least, was to try to clarify, if we could, the approach to peace negotiations from the standpoint of the other side,” Mr. Lynd said on the show. “My own personal way of dealing with the anguish, which I’m sure we all have about the war, was to feel that as a historian, perhaps I could help somewhat in clarifying some of these issues.”

Buckley demurred. He called Mr. Lynd’s trip a “little vacation” into a war zone by someone with a “very dim hold of reality.” The tone of their conversation disappointed Mr. Lynd. “I am seeking very hard not to sprinkle epithets, which I think you have once or twice,” he told Buckley, who replied, with a smirk: “Well, I’m not a pacifist. I’m not against epithets.”

Mr. Lynd, who earned his doctorate at Columbia University in 1962, was employed then at Yale as an assistant history professor. Yale administrators were incensed by his trip and his emergence as the “elder statesman of the New Left,” as the New York Times called him at the time. After calls for his firing by alumni and other professors, Mr. Lynd was denied tenure in 1967. He moved to Chicago, where he taught part-time at two local colleges but failed to land another tenure-track position at a major university.

“There’s no question in my mind that I was blacklisted as a history professor,” Mr. Lynd told Newsweek in 1978. “If you can find one that will hire me, I’ll retract the statement.”

Staughton Craig Lynd was born in Philadelphia on Nov. 22, 1929, to Robert and Helen Merrell Lynd, prominent sociologists and co-authors of the landmark “Middletown” studies of life in Muncie, Ind. As he grew up in New York City, Mr. Lynd attended the Ethical Culture and Fieldston schools. He graduated in 1951 from Harvard University and married Radcliffe student Alice Niles the same year.

In 1953, Mr. Lynd was drafted into the Korean War but served in a noncombat medic role as a conscientious objector. He was dishonorably discharged after Army officials discovered his membership in leftist groups while he attended Harvard. Mr. Lynd and his wife then moved to an ecumenical religious community in Georgia.

In 1961, hoping to play a role in the emerging civil rights movement, Mr. Lind got a teaching job at Spelman College, where he met fellow activist and historian Howard Zinn. He taught future novelist Alice Walker, who later called Mr. Lynd “her courageous White teacher,” whose activism was “always linked to celebration and joy.”

Mr. Lynd joined the Mississippi Summer Project in 1964, the first of many adventures in activism, but it wasn’t until his trip to Hanoi that he became a household name. After he failed to obtain another tenure track job in academia, Mr. Lynd went to law school, graduating from the University of Chicago in 1976. He and his wife moved to the Youngstown area of Ohio, where he worked in labor law and prisoner advocacy.

Mr. Lynd continued his work in history, writing several well-received books — some co-authored with his wife — on Marxism, slavery, racism, labor history, worker’s rights and a prison uprising. Commentary magazine called his “Intellectual Origins of American Radicalism,” published in 1968, “a major work in American intellectual history.”

In addition to his wife, of Girard, Ohio, survivors include three children, Lee Lynd, Barbara Bond and Marta Lynd-Altan; seven grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren.

In 2001, Mr. Lynd visited Kent State University during Black History Month to speak about his life fighting for civil rights.

“We did the best we could,” he said. But until the races truly come together, he added, “We aren’t going to be able to change things that disturb us in this society.”