Paul Morantz, a California lawyer who crusaded against brainwashing self-help gurus, crooked psychotherapists and menacing cults, including one that nearly killed him with a rattlesnake, died Oct. 23 at a hospital in Santa Monica, Calif. He was 77.

Mr. Morantz’s death was confirmed by his son, Chaz Morantz, who declined to provide a cause.

In taking on Synanon, the Church of Scientology, the Peoples Temple led by Jim Jones and a self-help group whose therapists beat their clients, Mr. Morantz fashioned himself as a modern-day Davy Crockett, defending righteous ideals even if his efforts put him in peril.

Mr. Morantz, his son said, would often cite a maxim attributed to the folk-hero frontiersman: “Be always sure you are right, then go ahead.”

Just out of law school in the early 1970s, Mr. Morantz said he felt directionless and was living in a $90-a-month Southern California apartment so barren that he was embarrassed to have guests. But one day in 1974, he received a phone call that spun his life, he later wrote, in “a direction I never would have suspected.”

The call was from his brother’s high school friend, a liquor store owner who said he knew an alcoholic being held captive at a nursing home in a government check scheme. Mr. Morantz decided to investigate, talking to nurses and others at multiple Los Angeles-area nursing homes.

Mr. Morantz discovered that elderly alcoholics were being sold for $125 to nursing homes by a man posing as a volunteer outreach counselor at the county’s drunk court. The nursing homes sedated the “captives,” as the Los Angeles Times called them, with Thorazine and collected government checks for their stays.

Mr. Morantz filed a class-action suit and won a $300,000 judgment. At least two of the people involved in the scheme served jail time for improperly referring patients to a health-care facility for profit.

The “captives” case, Chaz Morantz said, launched his father’s legal reputation. “My dad just hated bullies,” he said. “He wanted to stand up for people and help them fight back. He really had it out for sociopaths and other malicious leaders that took advantage of their followers.”

Mr. Morantz was praised in the media for his meticulous investigation and relentless legal maneuvering. Soon, clients were seeking him out.

In 1977, he was approached by a man whose life had been destroyed by Synanon, a California drug rehabilitation organization that evolved into a religious movement. Its founder, Charles E. Dederich Sr., viewed himself as a prophet and ordered his followers to undergo vasectomies and abortions and to physically attack enemies.

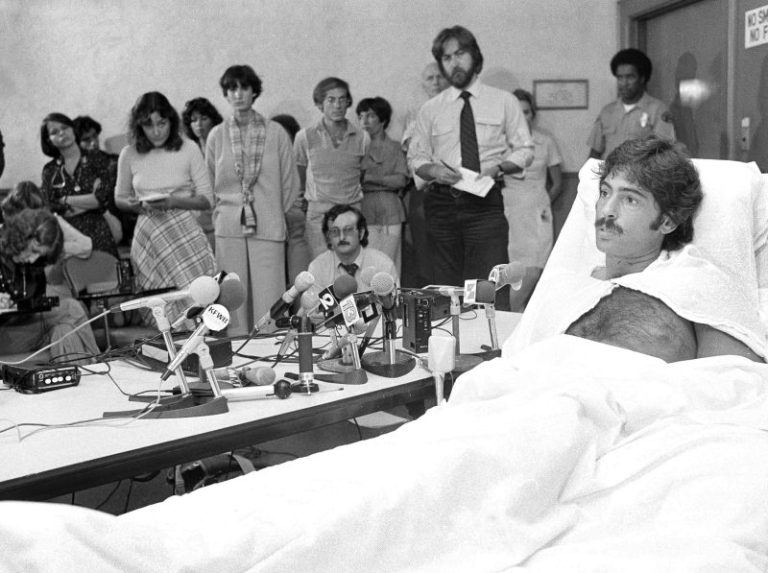

Mr. Morantz sued Synanon on behalf of several members who managed to escape. Three weeks after winning a $300,000 judgment, he reached into his mailbox at his Pacific Palisades home and a 4½-foot rattlesnake sunk its fangs into his left wrist.

“It felt like having my hand in a vise and it kept tightening,” Mr. Morantz told the Times from his hospital bed.

He managed to run for help and screamed to a neighbor about what had happened. The neighbor wrapped Mr. Morantz’s arm in a tourniquet while waiting for first responders.

As paramedics treated him, four firefighters beat the rattlesnake with shovels and chopped off its head. They discovered the snake’s rattles had been removed, meaning there was no warning sound to alert Mr. Morantz of the reptile in his mailbox.

The doctor treating Mr. Morantz, then 32 years old, said he was “extraordinarily lucky” to survive.

Dederich and two members of the group’s “Imperial Marines” hit squad were arrested a few days later on charges of attempted murder and conspiracy to commit murder. They all pleaded no contest, with the followers receiving a year in jail and Dederich, then in poor health, receiving probation. Dederich died in 1997.

A year after the attack, in a Times profile, Mr. Morantz said he wished he “didn’t know anything about cults.”

“I have no desire to spend my life worrying about cults, groups or movements,” he added. “On the other hand, just because you don’t want to be involved anymore doesn’t mean you can turn your back when someone asks for help.”

Paul Robert Morantz was born in Los Angeles on Aug. 16, 1945. His father worked in the meatpacking industry; his mother was a homemaker. There were signs during his boyhood of his future outrage at injustice, particularly when it came to religion.

“When I was 12, I listened intently during Passover services as the rabbi explained that wine and matzo should be left outside as a gift for the Angel of Death,” he wrote in his memoir, “Escape: My Lifelong War Against Cults” “Apparently, when the Pharaoh refused to free Jewish slaves in ancient Egypt, God put out a contract on the first-born son of every Egyptian family and sent the Angel of Death to carry out the hit. The angel ‘passed over’ Jewish homes, sparing those children.”

That night, Mr. Morantz got his baseball bat and tried to sneak out to defend the children. His parents caught him.

“I can’t believe you are all celebrating this,” he told them. “I can’t accept the idea that God would murder innocent children. I’m going outside to hide and when the Angel of Death comes for his wine and matzo I’m going to bash him so he won’t ever harm a child again.”

Mr. Morantz settled down and led an otherwise contented boyhood filled with sports and an obsession with the University of Southern California football team. After high school, he joined the Army Reserve and eventually enrolled at USC.

Mr. Morantz wanted to become a sportswriter, and he got a job working at the Daily Trojan, the campus newspaper. After he graduated in 1968, the Times offered him a job, but his girlfriend talked him into going to law school, which he did at USC, graduating in 1971.

His first job was as a public defender. It wasn’t for him.

“I left,” he later wrote, “… not liking getting off guys I would rather put away in jail for a long time.”

Mr. Morantz worked part time in his brother’s office while pursuing freelance writing projects, including a Rolling Stone story about surf music duo Jan and Dean that he later helped adapt into a TV movie called “Deadman’s Curve.” Then he got the nursing home call that changed his life.

Following the Synanon case, Mr. Morantz became a highly sought-after litigator for victims of cults and pseudo-religious groups.

He represented a father who tried to get his son back from Jones, the leader of the Peoples Temple, only to see those hopes end in 1978 when more than 900 members were killed during a murder-suicide event. In the early 1980s, he helped successfully sue the Los Angeles-based Center for Feeling Therapy, whose “therapists” beat their patients in a procedure called “sluggo.”

Mr. Morantz was also involved in helping ex-members of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church in a case in which the California Supreme Court ruled in 1988 that religious organizations could be sued for fraud. His clients alleged they had been tricked by church recruiters into attending a camp where they were subjected to mind-control techniques, including fasting and all-night lectures.

Mr. Morantz had many run-ins with the Church of Scientology, in court and in public.

In 1995, at a health fair in Pacific Palisades, Mr. Morantz was approached by a man who asked to speak with him about psychology. “He showed me a list of questions clearly displaying an anti-psychotherapy bias,” Mr. Morantz wrote. “Boy, did he pick the wrong guy.”

Mr. Morantz challenged him: “You’re Scientology.” The man denied it, saying he was just part of a group spreading word about psychotherapy abuses. The host of the health fair tried to kick the group out, but Mr. Morantz told her the Scientologists would probably bankrupt her in litigation.

“Let me handle this,” he said. “This is what I do.”

As the group put on a skit about electroshock treatments, Mr. Morantz addressed the crowd.

“The people speaking here have the right to do so,” he said. “They also have an interest in denouncing mental health professionals. They have that right. You have the right to know who is speaking. So I am telling you this is from Scientology. You can walk away or continue to listen, but at least now you will be clear as to the source.”

The crowd dispersed.

Mr. Morantz’s marriage to Maren Elwood ended in divorce. Survivors include his son and two grandchildren.

Despite his lifelong tangles with pseudo-religious groups and their prophets, Mr. Morantz never wavered from his belief that religion could be a force for good.

“Whether we worship single or multiple deities, Mother Nature or the Church of the Divine Meatloaf, our populace seems hard-wired to believe in some greater force,” he wrote in his memoir. “When groups use the power of peer pressure and brainwashing to control people and make them surrender their autonomy, their money or their moral compass, I feel compelled to step in.”